3000 palabras para T.S Eliot

1 Going deeper into the etcetera

The fact that nowadays we can still find clasicist authors, must not only not take us by surprise, but indeed make us realize how hard it must've been for new views to develope and make themselves space between the old patterns, understanding that this contrast is in fact its encouragement and principal incentive. End of the 19th century, beginning of the 20th: what do you exactely mean by Modernism?

Now that we know poetry will never tell us the world such as it is (should we find out by newspapers?), but as it should, -we read this a long time ago from Cervantes himself actually, and we find its real origin in the epic novel, however...- Now that we accept to play the game because something inside us tells us that's Truth; and learning that at the end of the day, it's all about mind's projection and the poem the reader needs... We may start recognizing this movement, at least initially, a as revolutionary response against the traditional parameters.

The very first seed related to this "war" can be founded on Kant's approachments, but let's skip a few steps 'til the case we're now dealing with.

What was poetry back then, what is it now, what will it be?

It's the same question with innumerable answers. Mines is hope.

Where do poems go once they've been read, where when they haven't? That's a different matter, but in any case, I guess to the back of our heads. Somehow that's what happens. There's a misterious sense down there giving us small clues of what exists already, what will, what should. We all carry that, within.

The word itself modernism is just an excuse to distinguish from and condemn old tendencies,

a provisional name for something boiling on desire but still under construction, even though there were voices and facts in the ambient, such as Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Gropius, Van der Roe and vanguards like surrealism and dadaism.

It certainly was a creative environment, a conceptual explosition of where art defines its way through the interwar and those concrete societies. It was a natural reaction facing the unbreathable circumstances.

Future was on their side. The promised land. New routes and possibilities to search for, challenging the past, burying it as the public reacted. Something big was happening.

Meanwhile, countries that still had the bourgeois point of view controling the scene (such as the U.S and the U.K), rejected whichever propposal of extreme freedom, since that could carry themselves problems, in the sense that they had themselves become a matter of criticism.

A good examples of this could be Metrópolis, by Grosz. A love/hate declaration to the city, a place that gives you all so later it can snatch it again away from you, leaving you worse that you were on the first place, embarassing you. That contaminates you with its toxic cynicism and hypocrisy.

There's no room for no one there. And at the same time, where to go, what's all the rush?

Can't you people relax and forget for a second about money and appearances?

And so it is, that on this frame of formal limitations and aesthetical posings, searching for beauty and genuine structures, we may fall with Yeats and Pound on the afterlife question that at this point they argued about: who's this poetry to? why should a poem finish? what's expected?

And that's when Prufrock by T.S Eliot comes to mind, because it follows Mallarmé's resolution

"a poem's made by words and not ideas", as well as the symbolist fashion, and the imaginists sounds (which ocasionally could've turn down as a dilemma: the musical phrase rather than the metronome; verses must be pronounceable!).

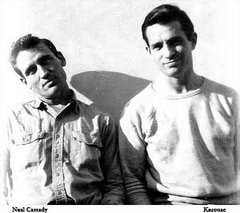

I understand through this poem why the Beat generation was also impressed. It has a very american atmosphere, almost like Whitmann. Woody Guthrie could've wrote it, or Bob Dylan.

It's as if you hear his voice all around.

It talks about indecissions, coffee, one-night stands, hotels, women that come and go, evokes gravity, includes dialogue, involves us in it...

And it's from 1917, you haven't read non of that until now. It's been considered the first modern poem in English language, and its key is the shape. Sharp and liquid at the same time.

Before this moment in time, it was clear the poet was creating the poem. Constructing it tear by tear. And in that exquisite context, the genious will make its way through 'til he bleeds to death.

The diference between now and back then, may be as simple as saying "I'm dying", instead of "my spirit's leaving me behind" for example. Both evoke death but have not quite the same meaning, do they? What's more true? It depends on the feeling when the time comes, and modern schemas are telling us about the moment in a complete exciting and realistic way. Without the flowery.

The reason why other writers hadn't gone that far before, may have been because of the reputation. Nobody wanting to be called vagrant, they rather smoke their cigarettes in large cafés, rather than crawl the streets looking for the soul and blood of the planet. Because that's not what you're supposed to do when you're an intelectual, is it? Because the rime, because the natural motifs... and sometimes coughing is better than day-dreaming. Going back to the experience, and not the platonic muse you may've been sure of having touched, but has she ever really touched you?

It's just another stile alright, but sometimes you rather scape from infinite tricks without a beginning or an end and try luck on the receiver's own contribution to finish things, or even fix them, been a little more humble. Eliot himself admited several times in public his insecureness, his doubdts. And didn't have a problem in asking a colleague such as Hayward to correct and help him out with the Four Quartets, for instance.

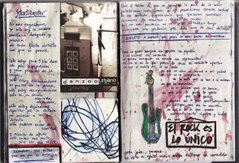

Maybe, and just maybe, that's what modernity's all about. Allowing the poem to flow by its own, becoming a puzzlement even for the writer. Leaving the instinct follow its way back home; heart rather than head. Letting it come if that's its destiny and not forcing it. Watching it pass by through the bar instead of on the paper without the fear of forgeting it even if makes you angry.

"Everything's poetry except for poetry", and the pain of its criticism.

New authors bet for simplicity without loosing the academic matters base. Much later think about the Beatles. Think about what Pop has made for the world: talking in a language everybody understands, accesible as the air, showing morality in the exact dose everyday-people will assume it.

But back to our issue, what we slowly suspect along the journey is that it's a mistake to look for the poem, to want it, just like been a poet, or even just been called one. To want to write a poem is the best way to destroy it. Or never give him birth. Non-born fire. In fact it's very pretencious to believe we're the owners of the poem and not the other way around, I mean, we're just a tool (Plato said). Ideas and inspiration are the ones that take possesion of us, we must never forget that. Like dreams. Like luck.

If we enter in the spiritual field, that's another tramp, but it gets even clearer: don't WANT anything, don't be so evil. Let it grow and come to you.

"You only know it once you've felt it" Bob Marley used to say.

You can't want brightness, nor understand it, nor envy it. We must stay human enough to accept whatever we already are. It's even tough work to learn from other, pathetic to copy, a crime to steal it.

It's something that once you know it is in you, you must just be patient and wait for it to posses you again. Like new friends come and incredible parties. The extraordinary can't be demanded if one's not lying to himself. If on top of all one is only guide by Truth, that is Art, that is Beauty.

That is shearing and Love, hope for tomorrow. Fresh air for magic.

Too many big words said together fastly, even, sometimes.

Poetry that'll come, when it is she that's waiting for you for once; poetry that's left to come.

That's what I feel about Modernity, and T.S Eliot had the intuition.

2 When to write your own Bible

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;

Petals on a wet, black bough.

"In a station of the Metro" by Pound

So much has been said about Eliot's political and religious beliefs, that sometimes I wonder if we're not losing sight of what's important.

He never denied his right-wing view of the world, actually, he gave "Authoritarian conferences" in which a fear of lower classes' progress was undeniable; nor that he had convirted into anglicanism because he wanted that faith, not because he had felt it (in an interview with A.Pellegrini around 1927). But, in my opinion those two factors of his personality aren't such a strong part of his speech. Otherwise I wouldn't comprehend him myself, at least not as much.

And moving on from the years he worked side by side with Pound during the gestation of The Waste Land (1914-1922), - we must here remember one of The Cantos leitmotifs: “Beauty is difficult”- adapting their techniques to imaginists' theories on economy, specified visual effects and complete formal freedom; “whispering inmortality” and other remarcable exercises; metaphorically one and metonimically the other; scaping from romantic and melancolic shall-we-say boredome from before; suggesting new answers about harmony in this hated and poisoned Europe; with an extremelly cultivated education when it comes to empiric and not pretended experiences, being part of the neorealism, guide by “art in less is more”, privacy mixed on elaborated emotion, etc; and looking for the most minimal and exact expression, in the sense that every single word written was as necessary as space and time, as concise as a brand new typewriter's calligraphy and, above of all, as natural and imaginative as you can get...

This time, our poet dares to move on from one anglosaxon country to another, to expel his demonds on a society that has truely disappointed him (during his lifetime were the two World Wars) and a finished marriage with Vivienne that lasted eighteen years, on Four Quartets.

3 Four Quartets itself

Technically speaking, we may consider the central skeleton of this extended text, a meditation about time and existance. And maybe go or at least look beyond/through it.

According to Esteban Pujals it would generally be structured this way: passing of time and the eternal moment - adult experience and its insatisfaction - a sort of purgatory where we get rid of our material/earthly needs - invocation of a divine intervention - and finally, finishing the poem on a close dependence to perfection, in order to achieve religious health. To fall asleep at night.

It's presented in a rather impersonal form which allows the use of our own representations, if it wasn't because of fantastical images already have been objectically insinuated together with beauty in search for that magical moment, and everythings floating around.

When it comes to style, that sinister irony tipical from the conservatism standards fades away as you open the book by any page and read something like: In the beginning is my end. In sucession

Houses rise and fall, crumble are extended,

Are removed, destroyed, restored, or in their place

Sometimes the use of extravagant icons can take us to confused places. We must count on the fact that even crazyness, illness, hunger, will be there for a reason. Everything's there on purpose. A catastrophe may be deliberated, in order to create something else. Those mortal remains are there to keep us alert.

It also make us think of all the lifes we chose not to live. What would've happened if...

Now it's useless to think about it, but still, maybe that can be called Beauty.

There's a constant feeling of overconsciense, as we felt with Dostoyevski's characters (which can be consider a disease: analyze too much the things that surround us). But that's in part the roll a writer suits himself in. He tries to control everything for a moment, for an electrical moment feeling eternal, with a cosmic vision. Being God and learning how to die. That's the only way to find Wisdom.

The frustration comes when "here you have your stupid poem, now what? what's next!"

It's painful the fact that life continues once you've already have reached some limits. You've felt Happiness and you knew in the very moment you were being blessed by that fortune.

Ocassionally Eliot's thread is almost invented or nonsense, but it must be there to follow the flow,

even if it's just by instinct.

The life of the words is their own musicallity, their destiny to die, such as ours, and every living criature.

Questions are asked to the wind, as if it was a riddle: there's a still point in the middle of all this ridiculous world spinning round, what is it? For me it's Thought.

There are astral aspirations which can be confused with some old white-bearded God, and that could be what was in Eliot's mind, but for me, he's going deeper into metaphysical matters. I relate it more on Buddhism and Taoism than a real Christian answer/argument(s).

He wants to continue 'til the end, and that's very dangerous, and the headaches, and the loneliness;

but that's why we're here for.

The moral message is commonly at the end of the poem.

And the more curious you dig, the faster you get burned.

Those are the things I think about when I see (in context):

To look down into the drained pool

(looking into ourselves and probably seeing how empty we still are)

[...]Except for the point, the still point

there would be no dance, and there is only the dance

I can only say, there we have been: but I cannot say where.

(love, peace, the miracle / you have to have felt it to understand it)

To be conscious is not to be in time

[…]

Only through time time is conquered.

(we're doomed to isolation)

Descend lower, descend only

Into the world of perpetual solitude

World not world, but that which is not world

(loneliness when you've reached on your own a spiritual point, and you know it)

And all is always now

(obsession about the present, and controling it at last, and transform it as we wish

but would it still be the present?)

Valuation of all we have been. We are only undeceived

Of that which, deceiving, could no longer harm.

(we must look through appearances)

The dancers are gone under the hill

(Sadness is here again)

[...] there is yet faith

But the faith and the love and the hope are all in the waiting

('til magic decides to come back, even if it's not really to stay

and the non-existing Forever, except for Death, as we now know of)

In order to arrive at what you do not know

You must go by a way which is the way of ignorance.

In order to possess what you do not possess

You must go by the way of dispossession.

In order to arrive at what you are not

You must go through the way in which you are not.

And what you do not know is the only thing you know

And what you own is what you do not own

And where you are is where you are not.

(this is a clear refference on his knowledge and admiration for the learnings of Lao-Tsé

oriental philosophies)

And the ragged rock in the restless waters,

Waves wash over it, fogs conceal it;

On a halcyon day it is merely a monument,

In navigable weather it is always a seamark

To lay a course by: but in the sombre season

Or the sudden fury, is what it always was.

(authentity will resist, truth can take anything, even the end of the world, or the civilization)

I sometimes wonder if that's what Krishna meant

[...]

That the future is a faded song

[...]

Pressed between leaves of a book that has never been opened.

(this can be considered religious, no doubdt, but as well deals with the misteries of time

slow things may confuse us, because we think they're here to stay

and the poet is the bird that answers to that song, he think he's listened a long time ago)

Along the way through the voices of children in the garden (Burnt Norton), the vision of a philosophical sunset (East Coker), the metaphors of life accused by rivers and misterious seas (Dry Salvages) and finally, the vanishing energy and old age (Little Gidding) we enjoy, as clear as pure, Eliot's capacity to intensify and celebrate -in spite of all- Reality.

4 References

- KENNER, H., The Pound Era, London, Faber, 1971.

- LEVENSON, M. A Genealogy of Modernism, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1984.

- PUJALS, E., La poesía inglesa del siglo XX, Cátedra, Madrid, 1980.

- ELIOT, T.S, Four Quartets, Cátedra, Madrid, 1987.

Freely (Devendra Banhart)

http://www.goear.com/listen.php?v=5bd7fe4

2 comentarios:

Can't you people relax and forget for a second about money and appearances? -just great silvi- the snece point, the view over eyes, over years, over read...

mira qué buen rollo: http://ca.youtube.com/watch?v=pa2DgyLLEhk&feature=channel_page

i´m yours even when we forget the night

Eres espectacular, me emociona...que bello ensayo! Tan bien orientado en las reflexiones,maravilloso..somos filósofos pequeña! Hippies in the time of existance..me flipa como piensas! Te kiero y pienso in the midnight!

Yours, Turo

Publicar un comentario